By THIRSTY

Mark Yost has

written for The Wall Street Journal for 25 years and is a regular

contributor to the Journal’s Leisure and Arts pages and its Book

Review. During his time at the Journal, he has also written for the

Editorial page and worked at the European Edition covering subjects as diverse

as the creation of the Euro, the war in Bosnia and international efforts to

curb money laundering by organized crime. He has run with the bulls in

Pamplona, Spain, done underwater archeology in the UK, ice climbing in Scotland

and cross-country skiing across the battlefields of the Battle of the Bulge in

the Ardennes. From appearances on Fox News, Fox Business, CNN, syndicated radio

programs and appearing in Oliver Stone’s documentary about the business of the

NFL, Yost brings a wide range of passions and experiences to his Rick Crane

Noir mystery series.

|

| Mark Yost's Rick Crane Noir Series |

Stay Thirsty

Magazine was honored to visit

with Mark Yost at this home in Houston, for this Conversation about the

greatest figures and films in the history of the noir genre.

STAY THIRSTY: Raymond Chandler.

MARK YOST: Chandler, to me, is the greatest noir writer of all time.

Others would say David Goodis, or Dashiell Hammett – whom we’ll get to in a

moment – but to me it doesn’t get any better than Chandler.

He wrote The Big Sleep,

which introduced us to Philip Marlowe. Together with Hammett’s Sam Spade, these

two characters are literature’s archetypal private eyes, both, not

coincidentally, played by Humphrey Bogart.

|

| The Big Sleep |

The Big Sleep is interesting, I think, because there are people who have

read it several times over, seen the movie, which, due to Hollywood decency

standards at the time, is even more opaque, and still don’t get all of it. I

don’t see that as a criticism of the book or the film, but a compliment. It’s a

whodunnit that’s ultimately solved, but still leaves questions.

Chandler wrote

three other novels featuring Marlowe, including The Blue Dahlia and The

Long Goodbye, both critical successes. Interestingly, Farewell, My

Lovely, was the second Marlowe novel but the first to be translated for the

big screen. But I would argue that it was Bogart’s Marlowe, first seen in The

Big Sleep, that is the image most people have of the San Francisco private

detective.

Of course, the

other big noir name I haven’t mentioned is James M. Cain. His novella, Double

Indemnity, was first serialized in Liberty magazine, a popular pulp

publication from the mid-1920s to early 1950s. Chandler and director Billy

Wilder collaborated on the script for Double Indemnity (1944), but

Wilder has admitted that the best writing came from Chandler. I would agree

with him.

|

| Double Indemnity |

Double

Indemnity has what is arguably

one of the greatest lines in all of literature – not just noir. When Walter

Neff, the somewhat hapless, love-struck insurance agent is driving up to the

house of Phyllis Dietrichson, the woman who will convince him to murder for

her, Neff says in the voiceover narrative, “How could I have known that murder

can sometimes smell like honeysuckle.”

I love that

line. So much so that when my son and I were on a baseball trip to Southern

California in 2013, I made a point of driving up into the Hollywood Hills and

finding the house, which is still there, which was used in the film. We parked

the car on one of the narrow streets, got out, and I made my son, much to his

embarrassment, take my photo in front of it.

STAY THIRSTY: Dashiell Hammett.

MARK YOST: We’ve already talked a little bit about Hammett. He,

Chandler and Cain were the pillars of pulp noir in the 1920s ‘30s and ‘40s.

They were all born around the same time; Hammett and Cain in the 1890s and

Chandler – I’ve always noted – a few months after the Jack the Ripper murders

in 1888.

While Hammett

is perhaps best known for creating Sam Spade, the hardboiled San Francisco

private eye played masterfully by Bogart, he also wrote The Thin Man,

introducing us to that most unlikely mystery duo, Nick and Nora Charles. But

many admirers – and Hammett himself – would say that his greatest work is The

Glass Key about a mobster devoted to his political protector. In fact, the

Coen Brothers have said it was the basis for their crime drama, Miller’s

Crossing. Of the three noir authors, Hammett knew best of what he wrote. He

was a Pinkerton detective for seven years. He once said that, “All my

characters are based on people I’ve known personally.”

But perhaps the

most memorable character in his books and screenplays is the city he loved, San

Francisco. It’s largely because of Hammett that San Francisco is known as a

prime noir locale. In fact, I dragged my poor son – again, on a baseball trip –

to a side alley in the heart of San Francisco where there’s a plaque that

reads, “On approximately this spot, Miles Archer, partner of Sam Spade, was

done in by Bridget O’Shaughnessy,” all characters in Hammett’s The Maltese

Falcon. The alley is just a few blocks from 891 Post Street, the apartment

where Hammett did most of his best writing and, not coincidentally, where Sam

Spade lives.

|

| The Maltese Falcon |

Although an

icon of noir, Hammett only wrote five novels, but three of them were good

enough to get him into the hall of fame: The Maltese Falcon, The

Glass Key and The Thin Man. Indeed, he was much more prolific and

well-known for his short stories and essays. In fact, many of Hammett’s

greatest characters first appeared in his short stories, including Marlowe and

the Thin Man.

Interestingly,

his creative burst lasted little more than a decade, from the early 1920s to

the mid-1930s. But Chandler said it best: “He was spare, frugal, hard-boiled,

but he did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all.

He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.”

STAY THIRSTY: Humphrey Bogart.

MARK YOST: If the authors mentioned above brought their characters to

life on the page, Bogart brought them to life on the silver screen. Ask most

people to close their eyes and imagine a private eye, and Bogart appears, either

as Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe.

|

| Dark Passage |

Beyond those

quintessential archetypes, I’ve always been a big fan of Bogart’s role in Dark

Passage, a 1947 film based on the novel by David Goodis. Bogart plays

convicted murderer (wrongly convicted, of course) Vincent Parry. He escapes

from San Quentin in a garbage truck and is soon picked up by Irene Jansen,

played masterfully by Bogart’s wife, Lauren Bacall. She hides him until he can

get plastic surgery, and then begin looking for his wife’s real killer. In a

bit of cinematographic trickery, director Delmer Davis shot the first 45

minutes of the film from a first-person perspective, so we never see Parry’s

face until he’s been transformed by a back-alley surgeon into Humphry Bogart.

But that’s where the gimmicks stop. After that, it’s pure Bogart and Bacall,

arguably at their best.

And then

there’s In a Lonely Place, the 1950 Nicholas Ray noir starring Bogart as

Dixon Steele, a long-in-the-tooth scriptwriter who has to take a piece of pop

writing and turn it into a screenplay to make ends meet. Gloria Grahame plays

Bogart’s love interest in what’s perhaps her greatest screen performance. It

languished for a long time, mainly because it came out the same year as Sunset

Boulevard and All About Eve. There also was some controversy over

the adaptation of Dorothy B. Hughes novel. But the film, thankfully, has been

rediscovered, so to speak. It’s included on a lot of best-of and must-see

lists, and in 2007 was designated “culturally significant,” one of the only

good things Congress has done in the past decade.

STAY THIRSTY: Billy Wilder.

MARK YOST: Wow! What do you say about Billy Wilder? Other than he did

it all and he did it all well. What’s sort of amazing about Wilder’s career is

that Double Indemnity was his directorial debut. It’s such a great film.

Fred MacMurray plays Walter Neff, the lead character, an insurance agent who

falls for the wife of a client and is convinced to murder her husband.

What’s always

been interesting – I think – for people my age (54) is that we grew up knowing

Fred MacMurray as Steve Douglas, father to Chip, Ernie and Robbie on My

Three Sons. Or, we knew him as the title character in Disney’s The

Absent Minded Professor. Then, one day, as adults, we stumble onto Double

Indemnity for the first time and go “Wow!”

Billy Wilder

was part of the wave of Jewish immigrants who fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s

and eventually wound up in Hollywood. In fact, I wrote about a great exhibit at

the Illinois Holocaust Museum about this exodus that gave us some of these

great talents, Wilder among them.

Wilder’s other

great film noir, of course, is Sunset Boulevard, starring William Holden

and Gloria Swanson. I’ve always found it interesting that Holden’s character,

down-on-his-luck screenwriter Joe Gillis, laments having to go back to the copy

desk in Dayton, Ohio, if he doesn’t find a project soon. This had to have been

a bit of an inside joke, since many of the great crime writers had once been

journalists – James M. Cain, G.K. Chesterton, Mark Yost (just kidding) – who

took the crime blotter they’d covered for years and turned it into great pulp

fiction.

|

| Sunset Boulevard |

Wilder, of

course, also directed the screen adaptation of Agatha Christie’s Witness for

the Prosecution. But he also had the depth and breadth to masterfully

direct the crime spoof, Some Like It Hot, starring Tony Curtis and Jack

Lemon as musicians who witness the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and go on the

lamb disguised as women in an all-girls band.

Wilder

collaborated again with Holden in Stalag 17. It’s principally a war film

about a German double agent, superbly played by a young Peter Graves of Mission:

Impossible fame, informing on the prisoners and their escape attempts. But

it certainly has the classic dark elements of noir. Holden plays an American

flyer wrongly convicted by the other prisoners of being the snitch. What ensues

is a clever game of cat-and-mouse to clear himself and indict Graves to the

satisfaction of his fellow prisoners. Once he succeeds, he basically gives the

finger to his comrades-in-arms as he hands them their stoolie and escapes in

the ensuing commotion. (Hope I didn’t ruin it for anyone who hasn’t already

seen it.)

STAY THIRSTY: Michael Curtiz.

MARK YOST: I asked that you include Michael Curtiz because without him

we really can’t talk about Casablanca, which I think is perhaps the

greatest film of all time. I’m going to be writing more about Casablanca

later this year for Stay Thirsty Magazine to mark the film’s 75th anniversary,

but I think there’s really a good argument to be made for it being one of the

great noirs of all time.

Many people see

“Casablanca” as a great love story, or a great war film, but so much of it is

about the cat-and-mouse – sorry to keep using that term – between Victor

Laszlo, the Resistance fighter played so well by Paul Henreid, and the Nazis.

Yes, there’s the love triangle between Bogart and Henreid and Ingrid Bergman,

but the crux of the story is really whether or not Laszlo will escape, and

whether or not Bergman’s Ilsa Lund will go with him, or stay with Bogart’s Rick

Blaine in Casablanca.

|

| Casablanca |

Casablanca wasn’t Curtiz’s only foray into the genre. In the mid-30s,

as another one of the European talents that had fled the Nazis and landed in Hollywood,

he directed Mystery of the Wax Museum, The Kennel Murder Case

with William Powell, and Jimmy the Gent, featuring James Cagney and

Bette Davis. He went on to direct Angels with Dirty Faces with Cagney

and Bogart. And then, of course, in 1942, Casablanca.

So, yes, Curtiz

was known for a lot of other things, but he was so talented and such a

significant force in Hollywood for four decades that to not include him in the

film noir genre would be just wrong.

STAY THIRSTY: Otto Preminger.

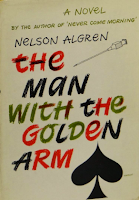

MARK YOST: I’m glad you asked me about Preminger because I am really a

big fan of The Man with the Golden Arm starring Frank Sinatra. I think

it’s some of Sinatra’s best work. It was made in 1956, sandwiched between

Sinatra’s career-defining performances in From Here to Eternity (1953)

and The Manchurian Candidate (1962). I would argue that “Golden Arm” is

right up there.

|

| The Man with the Golden Arm |

It was a

controversial film at the time because it’s about a heroin addict who goes to

prison, gets cured, and then goes back to his old neighborhood and falls back

into his old habits. It’s really a tragic story, and Sinatra plays it so well,

right down to the shakes and tics of an addict.

It was

controversial because it was in the 1950s. Yes, heroin had been around since

Westerners first discovered the opium dens in Hong Kong and Shanghai, but – you

Millennials should run for your safe space because I’m about to say something

that may offend you – heroin was really seen by much of society as a “black

problem.” White kids didn’t get hooked on heroin in the 1950s (they did, but we

didn’t talk about it). That was something that happened up in Harlem or on the

South Side of Chicago.

To their

credit, Sinatra and Preminger took on a controversial subject and showed a side

of the white, urban underclass that many people didn’t even know about. This

was before the so-called “war on poverty” and the civil rights movements of the

1960s. It was really a very brave and controversial film at the time.

The supporting

cast was great, with Eleanor Parker as Sinatra’s long-time girlfriend, whose

holding him back for fear of losing him; Kim Novak as the hat check girl at the

local tavern who has eyes for Sinatra, but terrible taste in men; Robert

Strauss, the great character actor who play Zero Schwiefka, the neighborhood

crime boss. But the biggest accolades should go to Darren McGavin, who plays

the neighborhood dealer. Whenever Sinatra tries to walk away from him, he

whistles softly and coolly says, “I’ll be around.” He knew – and, tragically,

we all knew – it was only a matter of time for Sinatra’s Frankie Machine. “Golden Arm”

also features a great jazzy soundtrack from Elmer Bernstein.

The other Preminger film that has to be included in any best-of noir list is Anatomy of a Murder, which came out just two years after “Golden Arm.” The first thing that drew me to this film was the locale. It’s set in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, a setting not unlike Upstate New York in my Rick Crane Noir novels.

Preminger

really cast against type here, so to speak. Typically, noirs have been set in

the big cities I’ve mentioned before – New York, Chicago, L.A., San Francisco. Anatomy

of a Murder was in a rural setting. For many people who live in the city or

close-in suburbs, they drive through these bucolic places – Upstate New York,

Michigan, the mountains of Colorado – and think they’re so innocent. They think

that the people who live in these small towns that are just stops for gas and a

bathroom break or a good, homemade meal at a quaint old diner don’t have the

same problems and pressures of people in the city.

WRONG!

Like “Golden

Arm,” Anatomy of a Murder was also very controversial because of its

subject matter: a rape case. Again, most big-city people don’t think things

like that happen in these small towns, but they do.

The film was

expertly cast by Preminger, with Jimmy Stewart as the small-town, folksy lawyer

who’s a lot smarter than we’re initially led to think he is. Lee Remick plays

the sexy wife and victim, while her husband, an Army lieutenant, is played by

Ben Gazzara. In short, Gazzara confesses to murdering a local innkeeper whom he

claims raped his wife. Stewart is hired to defend him, but spends most of the

trial trying to get the allegation of rape, the basis for his client’s

self-defense, admitted into evidence. Fighting him the whole way is George C.

Scott, playing a high-powered prosecutor brought in from the Attorney General’s

office to oversee the case. It’s a great, great film, and one of Preminger’s

best that’s often overlooked.

Link: