Vol. 111 (2021)

The Stephanie Chase Conversations:

Samuel Zygmuntowicz, Master Luthier

By Stephanie Chase

Guest Columnist

New York, NY, USA

Samuel Zygmuntowicz is a renowned contemporary American maker of violins, violas and cellos. (The term “luthier” dates at least to the 16th-century and derives from the French for “lutemaker;” makers of lutes eventually also made other stringed instruments of the violin family.) Born in Philadelphia in 1956, he began to study instrument making at age thirteen and later apprenticed with Peter Prier, Carl Becker, and René Morel. In 1980, his early reputation was cemented by the award of two gold medals for the workmanship and tone of his violins at the Violin Society of America Competition.

Instruments made by Samuel Zygmuntowicz are played by musicians that include the violinists Leila Josefowicz, Cho-Liang Lin, Maxim Vengerov, and Joshua Bell, and the cellists Yo-Yo Ma and David Finckel. The violinist Isaac Stern owned two violins made by him; following his death in 2001, one of these set a then-record price at auction for a violin by a living maker. The Emerson String Quartet played Zygmuntowicz instruments for their 2008 Deutsche Grammophon recording of Bach fugues, which is acclaimed for its “superb sound” (Gramophone). He is also the subject of a book, The Violinmaker by John Marchese, which documents his making a violin for Eugene Drucker, a member of the Emerson Quartet.

Zygmuntowicz is involved in cutting-edge technology for analyzing fine stringed instruments, and has published analyses of instruments that include the “Duport” cello, the “Titian,” and “Huberman” violins made by Antonio Stradivari, the “Plowden” violin made by Giuseppe Guarneri “del Gesù,” and a 1796 viola made by Pietro Giovanni Mantegazza. He has been interviewed and profiled by publications that include Forbes, The Strad, New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal, as well by National Public Radio. Since 1985 Samuel Zygmuntowicz has made his home in Brooklyn, New York, where he lives with his wife and two sons and enjoys playing fiddle in folk bands.

STEPHANIE CHASE: What led you to become a luthier?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I was a very quiet child. In school, I would sit in the back of the class and read the textbook or doodle, lost in my own explorations. My artistic hero was Rodin, and my earliest memories are of spending an immense amount of time reading, drawing and doing sculpture. I won a couple of awards in school art shows, and my family and teachers assumed I would become a professional sculptor. But I also had a microscope and was fascinated by the complexity and beauty of all living things; protozoa, onion skins, flatworms. When I was thirteen, I read a book that featured a violinmaker and I became obsessed with musical instruments, so I began to play guitar and banjo, then mandolin and, finally, violin. Instrument making combined my interests in art, science and music, and I never looked back.

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz (Age 10) |

STEPHANIE CHASE: Your background in sculpture and science, plus your musical abilities, seem ideal for your profession. What kind of training in making instruments did you have?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I first learned from books and built some instruments on my own. At sixteen years old, I got my first job in a violin repair shop, working directly with European-born craftsmen. After a few years, I fully committed and went to violin making school in Salt Lake City.

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz (Age 16) |

STEPHANIE CHASE: Tell us about this school.

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: The Violin Making School of America was founded in Salt Lake City by the German maker Peter Paul Prier, back in 1972. This was the first high-level violin making school started in the United States, and many of today’s good makers were trained here.

I was eager to work one-on-one with a master and was thrilled to work for a period with Carl Becker in Chicago, then after graduation I spent five years in the restoration studio of René Morel. Mr. Morel was famous not just for his restorations but also as a sound adjuster for the great artists of his time. He looked at violins not just structurally, but also trying to understand how they functioned and how the parts influence the whole. This close examination and analysis of form and function has remained the centerpiece of my own work.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Coincidentally, my father played a nice violin by Carl Becker, Sr., and I had several sound adjustments by Morel back when he was working in the shop of Jacques Francais. As you say, he was highly regarded as a virtuoso restorer and looked after many premier instruments played by international artists.

How have you developed the models for the instruments that you make?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: In the restoration shop I got to see famous violins by makers such as Stradivari and Guarneri from the outside and the inside, sometimes in pieces. The instruments I studied there have been formative and still influence my making style now. I would begin by copying a specific masterwork, and over time modify and interpret those models to my taste.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Approximately how many instruments have you made thus far?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I’m just finishing number 280, including violins, violas and cellos.

STEPHANIE CHASE: That’s an impressive number! About how long does it take you to make a violin?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: It takes about six months to complete a violin from when I start work. I sometimes make violins in pairs— it helps with flow to get the tools set up and I like the “sibling rivalry” of the two instruments in progress. The varnish process has long periods for curing and drying, so I like to also have another couple of instruments in the woodworking stages. A cello is a big project, which takes twice the time.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Could you please describe the basic differences between the Baroque violin of Stradivari's time and the way his violins are set up now?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: The changes from the Baroque set up are relatively minor, but they affect the playing style and sound. The bass bar, which is a kind of internal brace on the G-string side of the instrument, was smaller and lighter and gave a freer, more ringing sound. A baroque neck was set with a wedge-shaped fingerboard, adjusted to give the needed string angle, and was easy to grip. The modern neck and fingerboard are relatively streamlined, making it easier to reach higher positions, but one needs a chinrest to feel secure [during shifts of the left hand]. The biggest set up difference was in using gut strings, which give a clear and bright timbre with a textured “reedy” character, and which encourage a gentler bow attack.

STEPHANIE CHASE: You have made copies of some famous violins, including Isaac Stern’s Guarneri and the “Cessole” Stradivari. What did you find notable about these violins?

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz and Isaac Stern |

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: These copy projects were often commissions from amazing musicians, so their feedback became an important part of the process. For example, Isaac Stern’s Guarneri had an intensely focused sound in his hands, so I had to try capture the feel and sound for him to be satisfied. By contrast, Maxim Vengerov’s Strad has a deep, flexible low end with a sizzling brilliant high register, and his violin and his playing style were equally influential. And sometimes I feel the lingering influence of departed musicians like William Primrose or Fritz Kreisler when I study their instruments.

STEPHANIE CHASE: What are some of the factors in recreating these characteristics in a new instrument?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: We start with basic design, as far as outline shape and size; the wood choice, with variations in density and stiffness, then the arch contours, the thickness of the top and back, the shaping of the bass bar, texture of the ground coating and varnish, and so on. All of these factors create the structure, which determines how the finished violin will flex and vibrate, in very specific ways. Change the structure, change the sound.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Traditionally, the violins’ structures are created using wood forms, which can be either internal or external. Which kind do you use?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I usually use an internal form, similar to what the Cremonese makers used. With this system, you start with an idealized geometric design, but the maker has the opportunity to work freely and incorporate variations as they occur. It is also easy to modify and refine the forms before each use; I will add a few layers of paper tape to enlarge the form in spots, or file away a bit that seems excessive. I need that feeling of continued improvement and development.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Also, the internal forms are conducive to an original design, whereas the external kind would more likely be used by a copyist like J. B. Vuillaume, who apparently invented it.

What are some of the effects of aging and use on these famous violins, such as internal repairs and external wear?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: When studying old objects, one approach is to try to visualize the maker’s original intent. I find it more useful to view the instrument as a specimen, as it is, with all its modifications and repairs. As a former restorer and continual tinkerer, I know how powerful small changes to structure and set up can be.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Here you are referring to the more flexible factors such as the sound post and bridge, which are normally adjusted or replaced periodically in a violin? [Author’s note: the sound post is a small vertical post placed near the bridge inside the instrument and aids in transmitting vibrations between the strings, bridge, and the top and bottom plates of the instrument.]

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Bridges and sound posts are replaceable and vary with personal style and desired sound. For example, a tiny stylistic flourish in bridge cutting could change the weight or stiffness, which might maximize power and brilliance, or instead make the sound more mellow or even muted. Similarly, the position and fit of the sound post can change the balance between treble and bass, and even the resistance and focus under the bow. I don’t rely on rules or measurements for this – you have to experiment, listen, and follow the lead of the player.

Talking about Sound with Samuel Zygmuntowicz

STEPHANIE CHASE: Traditionally, violins are made principally from maple and spruce, with other woods used for linings and the fingerboard. What is the source for the woods that you use, and do you employ any special techniques for preparing these for use?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I use European woods that I have collected over time. In my studio, I have ceiling-height shelves, with stacks of wood arranged by year and type. For an upcoming project, I select the pieces depending on the tonal goals for the new violin, maybe more focused, or instead broader and deeper. Sometimes I need something visually unusual for a copy or special project, and I’ll comb my shelves for the right match. Early on my selection was by appearance or undefined “feel,” but now we’re able to calculate the stiffness and density of the wood before I cut into it, with much more control and consistent results.

STEPHANIE CHASE: How do you do this calculation?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: We can measure the rough block of wood to get the volume and weight, then calculate the density, how many grams per square centimeter. I also have a device that measures the speed of sound through the wood, which lets me estimate stiffness, all before I commit to using that piece.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Both maple and spruce are excellent conductors of sound waves, and I find it amazing that this was apparently known to the earliest violin makers in the 16th century!

There is often a rejection of violins that look brand new – whether by players or conductors of orchestras, for example. In replicating the external appearance of an aged violin, what are some of the techniques that you employ? Do you ever make instruments that appear new?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Making a new violin look old is a strange concept, but it has been part of making players comfortable using a new violin. When I antique a violin, I try to recreate the process that has caused a violin to age; all the handling, and wear and polish and patina. I actually find this a very creative process, using all the textures and colors available.

|

| Violin by Samuel Zygmuntowicz |

I also make fresh varnished violins, which lets the player participate in that process, where their own playing gradually creates the natural patina that builds over time. When my clients come in, I enjoy seeing the hand wear and pizzicato marks. The natural wear tells their story, that they are really making the instrument their own!

STEPHANIE CHASE: But I think we players feel a fair amount of guilt when we inadvertently bang up an instrument, and perspiration and the heat from the player’s neck alone can cause wear and tear.

What changes or innovations in your designs are unique?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I don’t seek to radically redesign the instrument, but I do have personal flourishes, like a distinctive “chevron” f-hole [sound holes are shaped like ‘f’s], and ergonomic small violas. I am continually refining my instruments, to maximize sound or ergonomics. The results may not be obvious, but all that optimization has helped me create a distinct and assertive sound. For example, most old violins have reinforcing patches to repair sound post cracks, but I install sound post patches on my new violins, both for damage preventions and for a specific tonal response.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Well, that’s interesting – usually these patches are added due to damage, such as from having too tight a sound post.

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Working in a restoration shop, I could see how much effect these structural modifications can have, and I try to use restoration techniques in a novel way, not for repair but as an enhancement.

STEPHANIE CHASE: How do you approach the arching of a violin? It forms the acoustical chamber inside the instrument, so is there a philosophy at work?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: The violin structure is complex and has contradictory requirements. A violin has to be flexible to produce low frequency sounds and yet be stiff to produce high frequency vibrations, all at the same time, and also be stable under all the constant string pressure. A flat top would collapse without support. An arch adds stiffness, and a more curved area can add localized stiffness, while a flatter area will encourage flexing. On a violin top you'll find a large variety of contours. But where should the top be stiff, and where flexible? The vibration movements are all too small to see with the unaided eye. The vibration videos in Strad3D literally show how and where the violin’s surfaces are bending and vibrating, in different patterns at the various frequencies. It is all there to see, and to try to decipher. In my making I now focus on arching in a much more informed way, and I’m better able to visualize how the finished top and back will behave in action. This is crucial, since the arching choices made at this step will determine the character of each instrument.

STEPHANIE CHASE: You mentioned the Strad3D project, which involves using pioneering technology for analyzing the sound responses of fine violins, such as laser vibration scanning. Would you describe this technique?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I collaborated with the physicist George Bissinger on Strad3D.org, which included the first 3D laser vibration scanning of Stradivari and Guarneri violins. This technology allows us to actually see what a violin does, not just how it looks. It is a type of motion capture, like PIXAR uses to animate live action. Similar technology is used in engineering and aerospace design. In this case, the Stradivari is vibrated, while a three-laser array shines beams of light at hundreds of points on the violin surface, recording the vibration at each point. Then the computer can create an animated 3d digital model of the violin, that moves and vibrates at any selected frequency, but much slower and more exaggerated, so that we see the true vibration patterns clearly. The moving images are almost shocking in their fluidity—one would never believe that wood could undulate like that!

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz demonstrating properties of the violin |

STEPHANIE CHASE: What do you, as a maker, extrapolate from this information?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: A maker builds a violin—a physical structure—that is intended to create a certain sound. We know the structure is incredibly sensitive, but we can’t see any of the action. Now we can see, actually see, what was invisible. As I look at the vibration animations, I have a flood of insights and observations—so, that is what the sound post does, that is how the bridge moves, that’s why the f-holes are cut with that shape. It connects the dots; the maker makes the structure, the structure determines the vibrations, the vibrations move the air into sound waves, the sound waves reach the ear and the brain puts it all together as music. As I said before, change the structure, change the music. That’s always been our goal. In practice, it is still tricky!

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz performing an acoustical text |

STEPHANIE CHASE: Does this technique have similarities to the experiments derived from those of Ernst Chladni?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Chladni was the founder of musical acoustics in the 1700’s, and he was able to show how separate violin parts move in specific patterns, or vibration “modes.” But he had no way to show how the assembled violin behaved, with far more complexity. Modern musical acoustics did not really advance until there were computers capable of digitally analyzing and processing sound. That allowed us to quantify the harmonics in sound that give us timbre, or to objectively compare instruments’ sounds. Vibration scanning and modal animation is a further step forward in structural acoustics.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Chladni tested the mechanics of the upper and lower plates of a violin; one kind of test derived from his work is to suspend a disassembled violin top or back over a speaker, through which various frequencies are sounded. The plate is sprinkled with sand or glitter, which form different patterns depending on how the plate responds to the pitch. Compared with the techniques afforded by computers, it now seems primitive – but for its era, it was a kind of practical experimentation that would be comparable to things like Galileo’s acceleration tests.

Is the work using laser vibration influencing the wider community of makers?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Many makers enter this field to avoid technology, so there has been some reluctance and suspicion to incorporating acoustics.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Yes, both makers and players are pretty much Luddites!

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: But there is growing curiosity and openness. I published Strad3D.org in 2009, and it has helped bridge the gap between scientists, makers, and musicians. The project includes CT scans, photography, traditional documentation, recorded music excerpts, modal analysis, and scientific articles, making it easier to connect the viewpoints. Also, it’s easier for a non-professional scientist like me to get involved. A laptop computer can use acoustic software, and now I even have a sound analyzer app on my phone!

STEPHANIE CHASE: I find this fascinating, partly because – unlike a piano – a violin has very few parts, and yet there is a need for this kind of equipment to analyze its responses. This doesn’t even go into how the design of a fine violin was originated.

Could you make a violin without using electricity?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: If I woke up in Stradivari’s workshop, I think I would function pretty well, as we both rely on hand tools and the basic methods haven’t changed that much. I’d be better off without my computer, though I’d miss the cd player, I suppose! And Stradivari would adjust fine in my shop, and he might even appreciate the power saw for rough work.

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz's work bench |

STEPHANIE CHASE: Yes, the front rooms of most violin shops have the workbench and small tools, but usually there’s at least a band saw in the back!

A number of famous fine violins have been owned by amateur musicians rather than professionals who used them in concert, and because I knew the former owner – who was a terrific violinist – I have a personal curiosity about the “Cessole” Stradivari’s interior condition; when you studied it, did you note internal patches and other old repairs?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Basically, all old violins have repairs, including sound post patches and new bass bars. The “Cessole” is well used but in excellent condition. I’d love to see it again someday, it was the first Strad that I closely copied and I still think of it as my “archetypical” Strad.

STEPHANIE CHASE: It’s a beauty – and what a great opportunity for a maker to study such a remarkable violin!

Earlier, you mentioned a special design for the f-hole; whenever I try to ascertain how a maker designs an f-hole it leads invariably to “maker X has a good tracing with measurements;” in other words, just copy that. How did you arrive at your own design? Because they are integral to the vibrating scheme, how do you know where to place them on a violin?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: The f holes affect the violin structure in dramatic ways. They cut the surface of the top leaving the area near the bridge freer to flex and move. A longer f hole will likely make the top more flexible, as will placing the F’s closer together. Strad3D has a video that I made exploring these variables.

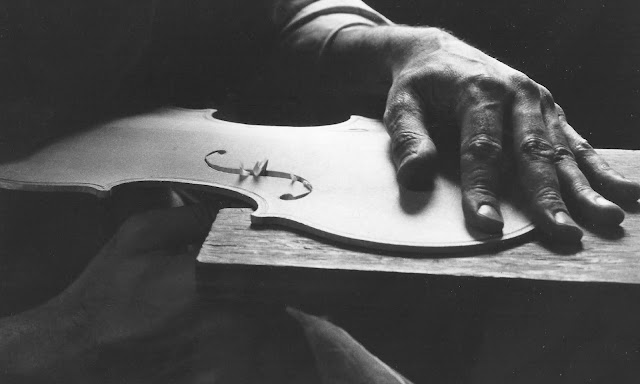

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz carving an f hole |

STEPHANIE CHASE: As an example of differences in sound holes; the violins made by Giuseppe Guarneri “del Gesù” (1698-1744) are exceptional in terms of their tonal projection, although many of them do not display the visual refinement of a Strad – and they do tend to have long sound holes.

How long does it take to “play in” a new violin for it to reach its optimal sound and response?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I expect my violins to sound good and be suitable for the stage from the beginning, but they certainly do change and develop. My clients find that the violin opens up within the first hour of playing, and there is a curve—rapid change in the first days and weeks, and more gradual development over time. The process should include seasonal adjustment visits and maybe a new sound post after the first humid summer.

|

| Leila Josefowitz with her Zygmuntowicz violin |

STEPHANIE CHASE: Like all objects made of wood, violins are subject to swelling in humidity! Most people don’t realize that they are designed to come open at the seams, should there be a lot of stress placed on it from substantial changes of humidity; otherwise they would be prone to major cracking, especially on the spruce top because it is a softer wood than the maple usually used on the back. What kind of glue do you use for the seams?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I use a special low-strength hide glue for the seams of the top. As you say, the glue is supposed to release before shrinkage could damage the top. Also, instruments may need to be taken apart for repair in the future, so the glue should be reversible.

|

| The inner form of a Samuel Zygmuntowicz violin |

STEPHANIE CHASE: Ever since Stradivari’s era, instrument makers have wondered what makes his violins so exceptional, which is why, in part, his instruments have been so closely copied. In the early 1970’s, the renowned Italian-American maker Simone Sacconi published a book on “The Secrets of Stradivari,” which is notable because he was among the first makers to attempt to analyze and codify the principals and techniques employed by Stradivari. Did his work influence yours?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Sacconi was the head of the [Rembert] Wurlitzer Restoration shop, and many great restorers trained with him there. My own teacher, René Morel, was a student of Sacconi, so I trace my lineage to him as well.

Sacconi’s book was a huge influence on the renewal of violinmaking in the 1970s. It was a closely observed study of Stradivari’s work, drawn from his experience as a restorer and maker, and a plausible reconstruction of Stradivaris working methods. It relied on his direct observations and deductions, stripped of mystification or superlatives. It inspired me to also go directly to the best-sounding instruments, and use my own observations. To me, modern imaging and analysis is just a continuation of that approach with newer tools.

STEPHANIE CHASE: For those who think that there is something almost miraculous about the great Cremonese violins, do you believe that all is now known about them?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: We may not know everything about Stradivari’s work, but we know enough, plus some new things as well. The Paris blind tests [in 2012] comparing Stradivari and modern instruments proved that most players and listeners cannot distinguish Strads from top modern violins, and they don’t reliably prefer the old violins either. This doesn’t diminish Stradivari instruments, it just confirms the effectiveness of his example, which we follow.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Personally, I’m not sure the “blind test” was done in the best manner, because it can take a long time for a player to adjust to a fine violin, and finding a bow that complements the instrument can take years. But back to Cremonese violins; is their greatness a matter of refined skills and excellent materials? How did these techniques originate?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: The 17th and 18th century in Italy saw an intense development and codification of the instrument as we still know it today. This includes the factors we have discussed; design, wood choice, arching, and varnish. I like to call this accumulated experience “C.V.T;” the Collective Voice of Tradition. This is always where I start.

STEPHANIE CHASE: This may also be a matter of knowledge that was lost and needed rediscovery in some form.

One of the so-called “secrets” of Stradivari has been his varnish; do you have a special formula that you use?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Varnish is a system, including wood preparation, ground coats, over coats and colors. I think the first coating that enters the wood is most important, and I do have my own formulas.

|

| Samuel Zygmuntowicz checking the tone |

STEPHANIE CHASE: I guess these are proprietary, understandably! Do you ever customize a violin according to a player’s proportions, such as hand size?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Oversized violins, misshaped necks and poor sets up are not only uncomfortable, they are dangerous. I always try to understand the players’ body mechanics and preferences.

STEPHANIE CHASE: That’s great, because the players can damage their bodies through poor form and physical tension alone. I have even spent many a lesson largely reminding the student how to stand properly.

The kind of bow used with a violin can make a tremendous difference in sound and articulation, even with two bows of the same length and weight, due to variances in balance points and wood flexibility. Do you ever advise your clients on matching a bow to their new instrument?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I suggest that my clients get their completed violin in hand before deciding on a bow. It is an individual choice but they need the instrument in hand. Fortunately, there are many great modern bow makers active now.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Yes, the process for making a fine bow is difficult but apparently not quite as challenging. But bows do have their own set of issues – for example, the Pernambuco wood from Brazil is endangered by the relentless deforestation there, and an international consortium of bow makers has been battling this problem for decades.

In view of your reputation, you must have a sizable waiting list for your violins. Making a violin is pretty much a solitary process, but how has the pandemic affected your work?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: I am lucky to have many great players on my list, so my work can go forward, but I deeply missed the immediate feedback of hearing my clients play for me in my studio, and optimizing my violins in real time. As things begin to open up again, I’m finding it surprisingly moving now to reconnect and hear fine playing once again in my studio.

STEPHANIE CHASE: In a sense, these instruments do not fully exist without being played and heard. This has been an especially tough time for musicians; in addition to the financial difficulties from the cancellation of concerts, we’ve also lost a major means of expressing ourselves.

But – thanks to the vaccines – things are starting to look a bit brighter. In a non-pandemic world, how do you like to spend your free time?

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Until the pandemic I played fiddle in dance bands. I love giving dancers the rhythm and energy to move. I feed off that interaction, and without listeners or dancers, playing music isn’t quite the same. I’ll be playing again soon, I hope!

STEPHANIE CHASE: It’s odd, isn’t it, to realize how much we depend on the listeners. And working with dancers must be especially rewarding.

To change the topic: I was very sorry to learn that your mother, Itka Zygmuntowicz, passed away last October at age 94. She sounds like an extraordinary woman; she was born in Poland and was deported at age fifteen to concentration camps that included Auschwitz-Birkenau. Yet she survived and overcame this terrible experience in a way that is profoundly inspiring.

SAMUEL ZYGMUNTOWICZ: Both my parents were Holocaust survivors who witnessed the darkest horrors of the twentieth century. That experience gave them a sense of intensity and the personal imperative to make one’s life count. My mother, Itka, gave witness as a speaker, singer, writer and poet, and still had a powerful and joyful life force. Fortunately, my own life has not had their tragedy or drama, but in my own sphere I also feel an imperative to work intensely, to try to understand what is below the surface, to serve others, and to tell my own story.

STEPHANIE CHASE: Your mother must have been very proud of your accomplishments! Thank you for sharing your story and superb expertise with us.

(Photos courtesy of Samuel Zygmuntowicz; Photo of Samuel Zygmuntowicz with Isaac Stern credit: Stewart Pollens; Photos of Samuel Zygmuntowicz building violins credit: Stewart Pollens)

Links:

|

| Stephanie Chase |