Vol. 112 (2021)

Five Questions for Author Rebecca Frankel

By THIRSTY

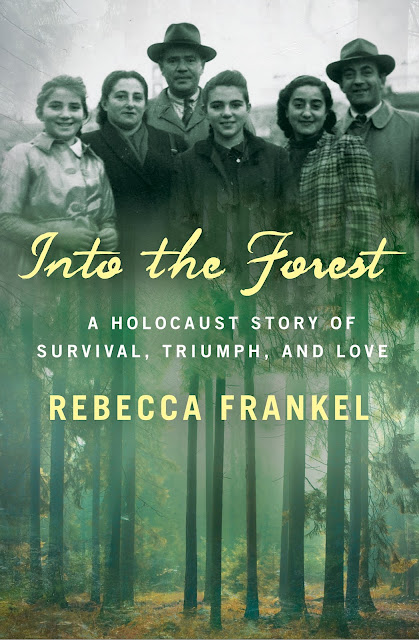

Rebecca Frankel is the New York Times bestselling author of War Dogs: Tales of Canine Heroism, History, and Love, and the former Executive Editor of Foreign Policy Magazine's print edition. A longtime editor and journalist, her work has received many accolades, including The George Polk Award in Journalism for Foreign Policy's story, "The Man on the Operating Table," depicting the devastating effects of an errant U.S. airstrike on a Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan.

Her written work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, National Geographic and The Washington Post. Her feature, "The Story of Dyngo, a War Dog Brought Home From Combat," about a retired Air Force bomb-sniffing dog that she adopted was featured in Smithsonian Magazine's issue, America at War.

She has been a guest on Conan, PBS NewsHour and BBC World News. A Connecticut native, she lives in Washington, DC, and that is where Stay Thirsty Magazine visited with her about her latest book, Into the Forest.

STAY THIRSTY: In your new book, Into the Forest, you chronicle a Jewish family that escaped extermination by the Nazis during World War II and traced their path to safety and prosperity in the United States. It is an inspirational story the pulses with emotion and a story of people who actually touched your life. How did you go about constructing this biography where you had such a personal stake? How did you maintain your journalistic distance and keep focused on the big picture?

REBECCA FRANKEL: In some ways, it wasn’t that difficult because my research was so heavily rooted in my own need and desire to understand not just the history of the Rabinowitz family, but in their Polish towns of Zhetel and Novogrudek (now located in Belarus), in their ghetto, and in the woods, and the broader history of World War II. And that meant, for much of my research, I was consulting as many sources as I could get my hands on—reported accounts, memoirs, interviews, and testimony, even Nazi memos. There was so much to learn.

I was fortunate that the story I knew was already so riveting and so profound, I just had to tell it—accurately and well. That was always my goal: to understand all the elements, all the rich details of things that happened not just to Morris and Miriam Rabinowitz and their daughters Rochel (Ruth) and Tania (Toby), but around them as well. As a journalist, accuracy, verifiability, fact-checking, etc. were my writing and researching guideposts, then came the writing and storytelling. And then back to fact-checking again.

I was never emotionally distant from this story and the people in the book—inside the Rabinowitz family and beyond them. I never felt I had to be. Investigating this family’s story of what happened to them during World War II and the Holocaust, and other Jewish families in Zhetel and Novogrudek or in the forest and the woods, meant a great deal to me not only as a storyteller but as a human being. I’m not sure that journalists (or non-fiction narrative writers) do their jobs better if they relieve themselves of their emotions, or their compassion and empathy.

But I did have to divorce myself from caring whether or not the family liked the book. Even though it would have been crushing to discover upon completion of the book and so many years of interviews and conversations, that Ruth, Toby, or Philip Lazowski (Rabbi, as I still call him), were disappointed in the final result or upset by what I’d written or how. But to let that concern guide me would have been compromising and problematic. That was the emotion I had to keep out of my work.

STAY THIRSTY: How did your themes of survival, triumph and love reveal themselves to you during your research?

REBECCA FRANKEL: Very quickly! I knew the story of Miriam Rabinowitz had intervening on behalf of then 11-year-old Philip Lazowski during the first ghetto selection (massacre) in Zhetel in April 1942. I also knew that it would eventually lead to a reunion between the families prompted by that fated encounter in 1953 in Brooklyn, and the eventual marriage between the boy Miriam saved and her elder daughter, Ruth.

What I didn’t know about when I first started interviewing Ruth in the winter of 2016, was the incredible circumstances under which her parents, Morris and Miriam, managed to keep their family together pretty much from the moment the war began in September 1939. Or how they managed to escape their ghetto, flee to the woods, and then survive in the forest—while leading a family camp of about two dozen others—for two years. They had a very strong marriage and love for each other and it’s the true center of their family and the story in Into the Forest.

I felt very strongly about including the word "triumph" in the book’s subtitle, because to me this family did more than just survive the Holocaust and the war, and this isn’t just a love story. Morris and Miriam and their daughters built new lives after they were liberated and they made a lot of new joy. I wanted to make sure that readers saw the Rabinowitzes as people who had a life before the war, and one after as well.

STAY THIRSTY: Irony and fate play major roles in your recounting of the Rabinowitz family's struggles and successes. How different would their story have been without those two forces at work?

REBECCA FRANKEL: Most of the Holocaust survivors accounts I researched had these forces at play. How could they not have? To escape Nazi execution, or to have freed themselves from the ghettos, or to have hidden without being discovered for days, weeks, months, and years on end while being hunted? It’s astounding anyone survived, let alone a family of four.

When it comes to the love story between Ruth Rabinowitz and Philip Lazowski, it’s hard not to conclude there was some greater force working to bring them together. It was well into our interviews, when Ruth told me that her friend Gloria Koslowski had been killed one week after the Brooklyn wedding where she made the connection between Philip and the Rabinowitz family, prompting the reunion between Miriam and the boy she saved, I was floored.

Though I think it’s important to remember that the origin of this connection started with Miriam and her decision to help a boy who needed saving, even though it put her and her daughters in danger. That was not fate. That was one woman’s conscious act of bravery and compassion. So maybe it’s better for us to view the ripple effects that action ignited not as fate—and I’m quoting the WSJ review of Into the Forest because it was phrased so beautifully there—but as "karmic righteousness."

|

| Rebecca Frankel |

STAY THIRSTY: As you look back on the five years you spent writing Into the Forest, what moments stand out most in your mind? What discoveries magnetized you emotionally and made you reflect on your life's arc vs. the Rabinowitz family's?

REBECCA FRANKEL: Watching dozens upon dozens (and dozens more) of Holocaust testimonies, all during the upheaval of the last U.S. election and then the pandemic, made for a lot of emotional research days.

Certainly, the moment Miriam decided to help Philip gave me a lot to think about beyond the work of reporting and writing that scene of the first Nazi selection in the Zhetel ghetto in April 1942.

I still think about her actions often, and not just because it altered the course of so many lives, but because I spent a lot of time wondering whether I would have done the same thing. To consider her act in hindsight then, yes, of course I would want to make the same decision she did… If I was ever in a postion where I had the opportunity to do anything like it, I hope I’d be able to follow Miriam’s example. The truth is, I have no idea if I could be so brave. Her instinct to help kicked in during the middle of a literal slaughter; there was so much violence and chaos, and the certainty that a false move would mean death. I don’t think any of us can know how we would behave in such a moment.

Then there was a brief description of a woman by the name of Sastonovich I came across in a collection of accounts documented just after the war. In it, an eyewitness who identifies her only by her last name, describes how knowing the Nazis were about to kill all the Jews in a field, this one woman stood up after being knocked down, and struck the officer who’d been beating her right across the face. Twice.

I thought about her a lot. I was just so arrested reimagining her last moments alive, how much defiance there was in her final act of picking herself up off the ground to face the policeman who’d been kicking her, and slap him so hard that she drew blood. Neither she nor the incident had a real connection to the story in the book, but I felt compelled to include a mention of her, and in the end, that right place was in the final lines of the Acknowledgements. I wanted to share the profound impact that this woman had had on me even though I’d only encountered a handful of lines about her in an old, out-of-print book.

STAY THIRSTY: In your past as the Editor of Foreign Policy magazine [FP], your portfolio was global and intense. How did you shift gears to writing your New York Times bestselling book, War Dogs? After leaving the magazine, did you ever miss the pressure and the pace of the international stage?

REBECCA FRANKEL: When I left FP the first time in 2011 to write War Dogs, transitioning to reporting and writing a book was a big jump for me: I’d been an editor at a desk for a long time. Most of the writing I’d done previously did not require a lot of field reporting, or any kind of structure beyond a longform magazine story. Then suddenly I was traveling around to military bases sometimes for days and weeks at a time, and that was all new and very much outside my comfort zone. But I loved it all. I’m so grateful for that time and experience. I was exposed to a world of people I would never have encountered otherwise. It’s also how I got my dog, Dyngo, who I had with me for four years.

I absolutely missed the FP newsroom and the wonderful crew of editors and reporters working on the magazine and web teams there—it was such a fun group of talented and smart journalists. There were lots of days of very solitary book writing that I missed the collaboration and pace of working on news (and breaking news) stories. I still miss the work I did as an editor and photo editor. I’m confident I did some of the most important work I’ll ever do during my time there (the coverage of the MSF Hospital bombing in Kunduz in 2015 with photojournalist Andrew Quilty is one series that comes to mind).

But the pressures of a 24-hour news cycle can be unrelenting; when you’re covering the entire world—as they do at FP—you’re beholden to pretty much everything that happens in one way or another. It’s an exciting job, and an important one, but it’s taxing. Book writing has its big-deadline looming miseries, but it’s wonderful to be able to explore something you find fascinating so thoroughly. As long as it’s telling good stories about things that matter… journalist, editor, author, I’m happy.

(Rebecca Frankel photo: credit Kiehart)

Link: