Vol. 113

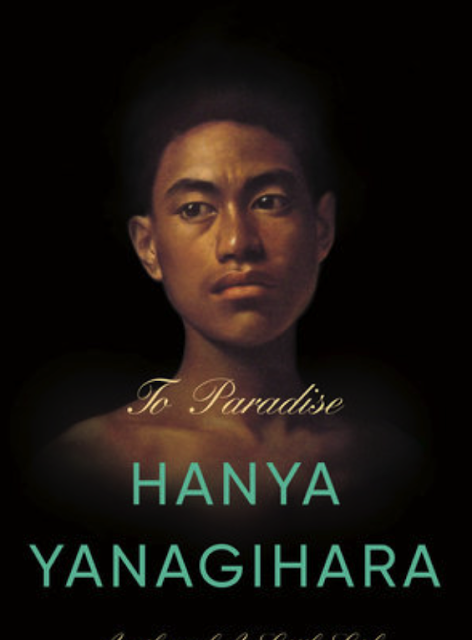

To Paradise

By Jay Fox

Asheville, NC, USA

Hanya Yanagihara’s To Paradise is a three-part novel set in an alternative timeline that explores themes of love, freedom, and historical identity. In each of these books, we come across at least one character named Charles, at least one character named David, and at least one character named Edward.

The first book takes place in 1893 and centers on the love life of the emotionally fragile heir apparent to a banking empire, David Bingham, who lives with grandfather in a mansion overlooking New York City’s Washington Square Park and must eventually choose between an arranged marriage with Charles Griffith, a man from an esteemed Massachusetts family, or an uncertain future with Edward, his lover. The second book starts in the same New York City mansion during the height of the AIDS epidemic (1993), where another Charles and another David (a/k/a Kawika) are having a dinner party for a dying man, Peter, but then shifts focus to David’s father, the heir to the Hawaiian throne, who also happens to be epileptic and named David (a/k/a Kawika).

The third book returns to New York City, this time in the twenty-first century, and tells the story of a family of Hawaiian (and Griffith and Bingham) ancestry torn apart by successive pandemics and politics. This final book is told from two perspectives. The first is through the eyes of Charles Griffith, a brilliant scientist based at Rockefeller University. Charles’ story is told through letters that he sends to his friend Peter between 2043 and 2088 and follows the collapse of civic society and the rise of a totalitarian state. The second is a first-person narrative of Charles’ granddaughter, Charlie Keonaonamaile Bingham-Griffith, who is left disfigured, emotionally flat, and intellectually challenged after being treated with an experimental drug during the pandemic of 2070. Charlie’s account describes life within this totalitarian state.

The rise of this regime does not take place in the United States as we know it. Within the world of the novel, the Thirteen Colonies failed to coalesce into a single political entity following the War of Independence, and instead split into two distinct nations sometime after the Constitution became effective but before the Bill of Rights was ratified. This initial split is roughly between North and South, though this divorce is not just due to the divergence of two distinct economies and cultures. While the southern states run on an agrarian economy that is based on the institution of slavery, and the Free States in the North have a nascent capitalist economy, the other major difference in this alternative timeline is that the Free States’ founders have adopted the teachings of an esoteric and utopian sect of Christianity that grants the freedom of men and women to love and marry whomever they wish. On top of allowing gay marriage, the Free States also have universal suffrage for all citizens, but this right does not include any Black or indigenous people—though the former group are allowed safe passage from the Colonies to Canada. Another peculiarity of the Free State is that arranged marriage is a thing, particularly among the elite. Finally, the Free States are not expansionist, whereas the Colonies are.

By 1893, when the first book begins, the geographic space that makes up the continental U.S. in our world has been splinted into at six separate: the Free States (Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and New England minus Maine, which is its own republic for some inexplicable reason), the Western Union (California, Oregon, and Washington), the Colonies (the South), and the American Union (which includes everything else except for Oklahoma, Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, which are labeled “Uncharted Territory”). The break between the American Union and the Colonies occurred following a civil war that probably happened in the 1860s. What goes on in “Unchartered Territory” is anyone’s guess.

By 1993, when the second book takes place, Hawaii has become a state, though the degree to which its history is different from our timeline is not entirely clear, nor is it clear how or why the restoration of the Hawaiian monarchy occurs sometime between the second and third books. It doesn’t really impact the story that much. In fact, most of the historical details that arise in the second and third books seem more ornamental than structural. One can forgive this in a 300-page novel. It’s difficult to feel the same way when reading a book that spans 700 pages and over 200 years and there is so much time dedicated to developing this alternative history in the first book. As a reader, I felt like I had watched someone spend hours setting up an elaborate domino run only to get distracted and wander off before setting anything into motion.

Meanwhile, the dystopian future Charlie describes in the third book of To Paradise feels trapped in the 1900s. It has all the trappings of an early-20th century police state as described by Arthur Koestler or a futuristic one as imagined by someone writing in roughly the same period (e.g., Yevgeny Zamyatin, George Orwell). The totalitarian state that she describes limits the flow of information and necessities to the public while relying on a massive surveillance system to monitor individual citizens and to then coerce them into doing the bidding of the state either through brute force or by enforcing a rigid hierarchy of privilege. Those who voluntarily submit and are useful to the state are given more privileges. Subversives, rebels, and others who assert their independence in any way are penalized either by loss of certain privileges or loss of life. Prominent apparatchiks within the state who develop a conscience or who have outworn their utility are publicly executed following a show trial.

Anyone who has studied totalitarian regimes from the first half of the 20th century (Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, Soviet Russia, etc.) or the current regime in North Korea will be familiar with this model. It is bad. What’s frustrating is that Yanagihara doesn’t seem to offer any new insights into the insidiousness of these regimes or the casual absurdity of totalitarian rule.

On their own, each of these stories is compelling and could have been crafted to stand independently. When taken together, however, the multiple lenses don’t align comfortably. One does not put down the book feeling as though they’ve glimpsed at something profound that could only come to light by incorporating multiple perspectives. The many Charleses, Davids, and Edwards don’t seem to be iterations or extensions of a larger archetype or shaped by the history of their heritage or name or some kind of tragic pattern that suggests the handiwork of Clotho. Rather, it’s as though Yanagihara knowingly introduced these reoccurring names as a form of apophenia.

|

| Jay Fox |

However, To Paradise is not entirely without a thread that courses throughout the novel to make for a compelling read. What ultimately unites many of the characters is a desire to create a paradise of their own, and that paradise is based on love, whether it be romantic love (David in the first book), filial love (the older David in the second book), or genuine human connection (Charlie in the third book). What makes them compelling is that they are willing to sacrifice, accept risk, and act with real courage to pursue love.

Yanagihara’s writing is at its best, and when her focus is at its tightest and most episodic. The retelling of a skating accident in Maine (courtesy of a letter from the Charles Griffith from 1893) or some of the family dramas between the Charles Griffith from the 2100s, his husband Nathaniel, and their son David define much of the third book and certainly stand out for their realism. Moreover, the tensions and ultimate antipathies between Charles, Nathaniel, and David is what made the third book by far the most engrossing of the three. Yanagihara demonstrates a mastery for showing the evolution of these complex family dynamics.

To Paradise is also the first novel I’ve read that seems to be influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, that seems to have taken some of the toll that the experience has put on each of us and imparted that sense of alienation to their characters, particularly Charlie. Charlie’s emotional vacuity speaks to the growing flatness of the pandemic experience, the hours spent in front of screens talking with coworkers, friends, and family instead of living situated in the world. Similarly, New York’s lifelessness in the third book should resonate with anyone who remained in the city during the initial lockdown of 2020. The streets were eerily quiet and gray and people you saw on the street seemed exsanguinated and defeated. It’s no wonder that Charlie’s Washington Square Park is a dead zone that had been stripped of its greenery like the killing fields between WWI-era trenches.

Perhaps Yanagihara’s most insightful passage concerns how time seems to stop in a pandemic. In the future, should we manage to avoid a harrowing timeline where consecutive pandemics and severe climate disruptions are the norm, people may read about the first months (or years) of the COVID Era as a time when history was unfolding at a rapid clip. For epidemiologists, public health officials, and politicians, things were certainly changing at such a frenzied pace that it was almost impossible to keep up.

For the average person, however, things were painfully static. You were in your apartment. You worked. You talked to same person day in and day out if you were lucky. You saw no new movies. You tried no new restaurants. You made no plans. You had nothing to look forward to. As Yanagihara wrote, “The world we live in now is about survival, and survival is always present tense…. Survival allows for hope—it is, indeed, predicated on hope—but it does not allow for pleasure, and as a topic, it is dull.”

Link:

____________________________

Jay Fox is the author of The Walls and is a regular contributor to Stay Thirsty Magazine.