Vol. 111 (2021)

A Conversation on Clubhouse with

Literary Lion

Jerome Charyn

Moderated by Dusty Sang

Recorded: Wednesday, May 5, 2021 @ 7pm

DUSTY SANG: Good evening and welcome to the first edition of Stay Thirsty Presents: Conversations on Clubhouse with Fascinating People presented in conjunction with Stay Thirsty Magazine whose guiding manifesto is to keep our fingers on the pulse of contemporary expression and to introduce you to some of the most interesting and accomplished people on the planet. I am Dusty Sang, Publisher of Stay Thirsty Magazine, and I will be your moderator for this program. Please note that the program is being recorded.

Now, it is my great pleasure to introduce tonight's guest – Jerome Charyn. Born and raised in the Bronx, he graduated Columbia College in 1959, cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa.

Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Chabon called him "one of the most important writers in American literature."

New York's Newsday hailed him as "a contemporary American Balzac."

The Los Angeles Times described him as "absolutely unique among American writers."

And the New York Times said, “Charyn has trained his prose and makes it perform tricks. It’s a New York prose, street smart, sly and full of lurches, like a series of subway stops on the way to hell.”

Mr. Charyn's first novel, Once Upon a Droshky, was published in 1964. He attracted wide attention and acclaim for Blue Eyes in 1975, the debut of his detective character Isaac Sidel. By 2017, Mr. Charyn had published 37 novels, three memoirs, nine graphic novels, two books about film, short stories, plays and works of non-fiction, which now total well over 50 books.

Two of his memoirs were named New York Times Book of the Year. He has been a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in Fiction, received the Rosenthal Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and has been named Commander of Arts and Letter (Ordre des Arts et des Lettres) by the French Minister of Culture.

His literary agent is the legendary Georges Borchardt who introduced the work of Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco and Jean-Paul Sartre to America.

Mr. Charyn has held a myriad of jobs while he achieved his prodigious output of books:

1. Recreation Leader, Department of Parks, New York, early 1960s;

2. High school English teacher, New York, 1962–64;

3. Lecturer in English – City University of New York, 1965;

4. Assistant Professor of English – Stanford University, 1965–68;

5. Assistant Professor, 1968–72, Associate Professor, 1972–78, Professor of English, 1978–80 City University of New York, Bronx, NY;

6. Mellon Visiting Professor of English, Rice University, 1979;

7. Visiting Professor and Lecturer in Creative Writing, Princeton University, 1981–85;

8. Visiting Distinguished Professor of English, City University of New York, 1988–89;

9. Professor of Film Studies, American University of Paris, Paris, France, 1995–2009.

In addition to his writing and teaching, Mr. Charyn is a tournament table tennis player, once ranked in the top ten percent of players in France.

Now, it is my distinct honor and great privilege to welcome one of the true literary lions of the 20th and 21st centuries to join us tonight. Our Conversation will be wide ranging on subjects from writing to the movies.

DUSTY SANG: Jerome Charyn, welcome.

JEROME CHARYN: Thank you Dusty.

DUSTY SANG: So, let's start with your latest book, Sergeant Salinger. Publishers Weekly, in a starred review, said it was "... a literary tour de force. Charyn vividly portrays JD Salinger's journey from slick short story writer to suffering artists. The winning result humanizes the legend." And Kirkus Reviews said, "The supremely engaging novel leaves us with a new, sometimes heart-rending understanding of Salinger and the times in which he came of age."

Why did you pick JD Salinger to work on?

JEROME CHARYN: Well, when I was a high school student, who had never read a book in his life, I was suddenly introduced to a Middle-class culture at the High School of Music and Art and all of the other kids kept talking about JD Salinger. And they said I looked like him because I had big ears and they must have met him, so obviously he had a kind of phantom presence in my life. And then later on, after I read For Esme with Love and Squalor, I realized it was a war story where you had no warriors and it completely overwhelmed me. And fifty years later, I decided to write about him. Not about the Salinger who was recluse, but about the young Salinger who dated Oona O'Neill and went through World War II. So I had his big ears. We both had the same first name, Jerry. And it gave me a great deal of pleasure to write this novel. I don't know why, but I wasn't trying to usurp him. I wasn't trying to become him. I didn't envy him in any way. I just tried to explore him. It's always a job of exploration.

DUSTY SANG: Your first chapter in the book is absolutely fascinating and magnetic. How did you come about that as the first chapter?

JEROME CHARYN: Well, I'm glad you liked it because so many people didn't. And I insisted on that opening and my French publisher wanted to take it out. Oona O'Neill was the sort of debutante of the year at the Stork Club. And the name Sherman Billingsley when I was a kid always fascinated me. And whenever I joined a club, I always said my name was Sherman Billingsley. So it was a logical place to start the book and Oona always went there. And Salinger also. He was called Sonny at that time. He went there with her and I thought it was a great place to start the book. To show her ... you start with the word "voluptuous," and I spread it out like an accordion because I wanted to sort of enter her world. Remember, no matter who you're writing about, it's always about language, and only about language.

DUSTY SANG: Let's talk about that for a second. You grew up in the Bronx.

JEROME CHARYN: Right.

DUSTY SANG: And you have said that in your early years, there were no books, there was no language. This is something that you had to discover yourself over time.

JEROME CHARYN: Yes.

DUSTY SANG: How do you and your brain work in producing language and producing the written word?

JEROME CHARYN: I really don't know. Because at some point in France, someone looked into my brain. I was having a ... maybe they thought I was going out of my mind. And the person who gave the test said he had never seen so much activity in the human brain in his life. There were so many connections that he couldn't quite understand. And I felt the same way about the paintings of Basquiat. If you look at any of his paintings, there's so much going on. There's so much power. There's so much lyricism that ... he obviously at some point had to stop painting. I originally began as a painter. I went to a store and I bought, like Van Gogh, I think we saw the film Lust for Life when Van Gogh cut off his ear, and I bought an oil painting set and I went to the High School of Music and Art. Immediately saw I had no talent whatsoever. I was among a bunch of geniuses. So I moved from the painted word to the written word because painting is a kind of language. I was painting with words, though I never read a book in my life. I remember the Reader's Digest had ... fifty ways to a more powerful vocabulary, and they would always give you like ten new words, and I didn't know any of them. I had to grovel to find language. But once I did, I began to see that language had a kind of music and you had to master that music and it was a lifelong job. You're always an apprentice. I remain an apprentice. Now, no matter what I'm working on, you're always learning. And that's the only pleasure that you really have.

DUSTY SANG: Do you find that your brain runs away with you at times where you have so many thoughts, your imagination is so vivid, that it's sometimes hard to control and discipline?

JEROME CHARYN: Well, that's not a bad thing because when you're writing a story, or whatever it is, and it can go in thirty directions, and in the morning, you don't know which direction it's going to go and by the evening, you've solved that problem somehow subliminally in your brain. You need all these circuits in order to tell a story because it's not ... it's very difficult. I mean ... writing a novella about crime and dealing with the various ways that that story may go ... you need all of these open circuits. So even though I am a little bit crazy and depressed all the time, I'm very glad that those circuits are open and that the imagination is still working. It's endless. I remember as a kid of seven, the teacher always put me up at the front of the class to tell a story and, like Ali Baba, I could just endlessly go on. It didn't matter ... the imagine ... in other words, the imagination was the only thing I had to fill a void. I grew up in a community where there was no language, no newspapers, I didn't even know that the New York Times existed. So in order to fill that void, you have to have an imagination. And that ... sometimes when you're depressed, it can leave you for years. I mean, there were years when I couldn't even write a word. But then there were other years, when I lived in both Paris and New York, and I had a computer in each place. And the minute I arrived in Paris, I started writing, then I got on the plane, and the minute I arrived in New York, I finished the sentence. Either the music is there or it's not there. And there's nothing you can do about it. When it's not there, you can't function, and when it's there, it's functioning all the time.

DUSTY SANG: Did you ever feel anger about your upbringing and the deficits that you had in terms of education because you had to do so much on your own?

JEROME CHARYN: It wasn't the poverty, Dusty, the poverty ... one could live with poverty, but my parents were both crazy. And the thing is that they had no language whatsoever. I remember as a boy of seven having to fill out forms for Con Ed or whatever it was. So when you're living in a landscape that's not sane, it's very difficult to function and you don't grow up. I never grew up. I'm Pinocchio. You know, I'm Pinocchio, and Lenore's sitting next to you and she'll tell you I can't even sleep when I broke six dishes today and I didn't know how to sweep them up. I didn't know what to do. I was completely lost, completely bewildered. But if you put me in a room and you say, Jerome, I'm going to kill you if you don't write a novel in one day, I'm not going to be afraid, Dusty. I may fail, but I'm going to do the best I can. It's not going to frighten me. And everything ... getting on a plane frightens me ... going to an airport frightens me ... but writing doesn't.

DUSTY SANG: Your older brother was your hero in many ways.

|

| Harvey Charyn (Jerome's Brother) |

JEROME CHARYN: Yes, he was, and I was very lucky in that my older brother, who should have been jealous of me, because I remember sitting there when I was five and he was eight, and I was eating by myself, and my mother had to feed him as if he were ... I was called "Baby," but he was the baby. But, on the other hand, he loved me, he really loved me. And the day he died, I remember I told him that I loved him. And that was the most emotional point in my entire life. I mean, it's so difficult for me to use that word, and I was able to say that because he saved my life, and I couldn't save his. I couldn't help him. But I wanted him to know that I loved him.

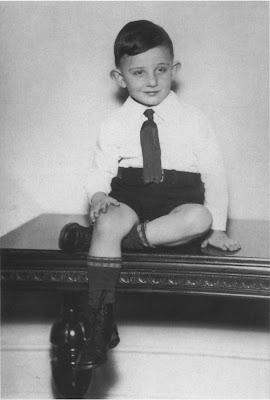

|

| Baby Charyn |

DUSTY SANG: Did any of that feed into your depression? Have you drawn upon your feelings when depressed for some of the characters in your books?

JEROME CHARYN: No, I don't think so. I think, Dusty, you obviously are not a person who is depressed, or you would know what depression means. Depression means that you cannot function, and when people kill themselves, and they say, Oh that person was fine in the morning ... everything is removed from you ... your psyche, your strength, your willpower. You're helpless, you're alone, and then it lifts, and it's gone. And when it's there, you just can't function whatsoever. And it comes back and then you know, as I say, there were years I couldn't write a word. And there were other years, I remember teaching at Princeton, finishing a novel in the morning, and while I was on the train to Princeton starting another novel, because I had it in my head. The lyricism is there or it's not there. I'm hoping to write a novel about Maria Callas. I watched the documentary about her and heard her speak and then hearing her sing in Norma was a revelation. I mean ... the whole notion of opera. So it's something I'm going to have to learn. You see, I now have a new task. For the next year, I have to learn opera in order to write a novel about Maria Callas.

DUSTY SANG: You spent a great deal of your life teaching others creative writing ... teaching others English. What was the greatest reward that you received in that relationship between teacher and student?

JEROME CHARYN: I received no reward teaching writing. I hated to teach writing. What I did like to teach was film and I absolutely adored teaching film. I mean, I would sit in a class, or I would watch a film with the students. And I would say, "When you talk about this film, don't say anything that's outside the frame. You just tell me what you see inside the frame. And that is the only discussion we're going to have." So I ended up teaching film. I started a film department at the American University of Paris. And I remember always walking out of the classroom with a tremendous elation because I was doing ... I wasn't a filmmaker ... I didn't pretend to be a director ... I'm a writer ... and teaching writing as a writer to me was not pleasurable at all. But teaching film was incredibly pleasurable because I could then enter into the landscape and not feel that in any way I was involved as a maker of films. I was only a watcher. I'm a watcher. I look at things. I examine things.

DUSTY SANG: You wrote a wonderful book called Movieland.

JEROME CHARYN: I'm glad you thought it was wonderful, because ... I mean, the Germans loved it. But on the other hand, it did not receive the recognition that I would have liked to receive.

DUSTY SANG: At the end of the book, you have a quote talking about Hollywood, and I want to talk more about Hollywood, get your opinions of things, but the quote is: The stars had everything and nothing at all. That was the sadness of Hollywood, their own worlds couldn't compete with the movies they were in. They could never be quite so large as their movie selves. So you saw in the movies, in some ways, in the culture of making movies, a sadness.

JEROME CHARYN: Yes. And right now, I'm finishing a novel on Rita Hayworth and Orson Welles. And I remember when I went out to Hollywood and walked on Hollywood Boulevard, and went to Hollywood and Vine, like a teenager, I felt like a kid. Like someone from Arkansas going up the Empire State Building. I mean, Hollywood Boulevard was a revelation to me. The only reality I had as a child was Hollywood. I mean, if you went to the movies twice a week, you could see every single film that was made during that year because there was always a double feature, so you were seeing four films. And you never came in at the beginning, you always came in in the middle. And after a while I could intuit from the ending of the film, how the film was going to begin. So I mean, I did teach myself ... it's really strange ... you can teach yourself so many things that you're not aware of.

DUSTY SANG: One of the things that you touch on is the movie culture that was created from nothing by the locals. And how people learned from the movies how to do things. Dating, kissing ...

JEROME CHARYN: ... and holding a knife and fork because as a kid I ate with my hands and then suddenly I saw Clark Gable cutting a piece of steak and still today, if you sit me in a table, I couldn't tell you where the knife should be or where the fork should be. And I remember being in love with someone and we were eating, and she cursed me out for not knowing where the knife and fork was. And it was the only time in my life, there's only one time in my life, I became angry and I said, "Look, I work very hard at what I do and I don't give a damn where a knife and a fork should be on a table."

DUSTY SANG: While you were teaching Film Studies in Paris at the American University, what was your curriculum like? What were you trying to do during the school year?

JEROME CHARYN: I was trying to learn. In other words, I invented all the courses. If I wanted to learn about documentary films, I had a course on documentary films. If I wanted to learn about the Western, I had a course on the Western. I was the first one to teach a seminar on Quentin Tarantino. And I can tell you, as we sat there with these twelve students, and remember, these were all outcasts, these students, they weren't from Yale and Harvard, they were kids who couldn't make it somehow and came to Paris. They all wrote wonderful papers about the music in Pulp Fiction, about strange subjects in Tarantino's work. And when I saw Pulp Fiction, I said, My God, he's doing a film exactly the way I write a novel. Reality can go wherever it wants. You can kill off a character and bring him back to life. Five minutes later, anything is possible.

|

| Jerome Charyn |

DUSTY SANG: With respect to movies, then and now ... the days of the studio system, the contract players, MGM cranking out 102 movies a year ... to now a very decentralized Hollywood which is competing with the likes of Hulu and ...

JEROME CHARYN: ... Disney plus. They are not millionaires or billionaires, they're trillionaires. In other words, you have so many ... if you're asking me how to compare the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood to what's here now, there was no Golden Age. Remember, there was tremendous racism. I remember when Hattie McDaniel won the Academy Award for playing a slave, a house slave, in Gone with the Wind and giving a speech. Black people didn't exist. They were invisible. It was a completely white-upon-white landscape. It was a world of indentured servants. It is true that the actors were treated as a kind of royalty, but they were royalty who were also servants at the same time. When you have a film about Hollywood, and talking about Hollywood and its Golden Age, one has to be very, very careful.

DUSTY SANG: But with respect to the cultural landscape, if people learned from the Golden Age of Hollywood how to hold a knife and a fork, how to smoke a cigarette, how to make love, and then the studio system was broken apart because most of the moguls, who started out in exhibition as theater owners and migrated to become the producers of movie they then showed in their own theaters, became too powerful ... and today, you don't have that vertical integration in the same way, but you have Netflix controlling the distribution to its Netflix subscribers, as well as controlling the manufacturing. And so, is it not much like the studio system of old where you have a few companies controlling the entire process?

JEROME CHARYN: Oh, absolutely, except that the system is so much larger. I mean, if you go ... if you have visited Hollywood and you go to Paramount and you go to the Columbia Ranch, it was a very small landscape. Netflix is a spider that's all over the world. I mean, these are ... in other words, you could make back ... I was saying to a former student of mine, if you wanted to do a James Bond film, just show it on Netflix for one evening and charge $50 and you'll not only make a profit, you'll make enough to do another James Bond film. So, in other words, the landscape has changed. But it's a much larger landscape. It was much more quaint in the day when there were seven-year contracts, and Clark Gable refused to make a film or whenever it was, these were control ... it's the same thing ... look what happened in basketball when you had the notion of free agents. Before you have free agents, you were an indentured servant to a club, and they could trade you wherever they wanted. Now, LeBron says, "I want to play in L.A. ... I'm going to play in LA." And he can play anywhere he wants. If he wants to go to the Knicks, which I would love, he'll go to the Knicks. So the players here, in some sense, also control the landscape. What has happened, everything has been monetized. It's all about money. It's all about the kingdom of money.

DUSTY SANG: Same thing sort of happened in Hollywood when the agent class came alive.

JEROME CHARYN: Yes.

DUSTY SANG: The agents then became the controllers of the talent.

JEROME CHARYN: Absolutely.

DUSTY SANG: And the studios started to lose their control. I think Jimmy Stewart in Winchester '73 was the first actor who got a piece of the actual box office of a film. But as these actor contracts expired after seven years, the Lew Wasserman's of the world, and Jules Stein, came forward, gave the talent a home and suddenly controlled all of the talent over a period of time.

JEROME CHARYN: Absolutely. The agent became much more powerful than the new producer not only in films and books and everything. You even can't submit a book without an agent. It was such a quaint world. It was a recognizable world. It had all its prejudices, which it still has now, but on the other hand, it was recognizable. It's no longer recognizable. Where is Disney? Disney is everywhere. Where is Netflix ... under the table? It's inside your modem. It's everywhere. You can't escape it.

DUSTY SANG: As you look at the films that are being made today, culturally, versus the films of the Golden Age, are the films of today going to have the durability, that the films ...

JEROME CHARYN: ... they're awful. They're awful. The films of today are awful. We live in, forgive me for saying this, in a very mediocre time. Why? Why do we live in such a mediocre time? I don't want to get into politics, but there's something wrong with our culture. There's something you know ... cancel culture ... the whole notion that you can say certain things and you can't say other things. Men can no longer write about women, women can no longer write about men. I mean, the limitations of the world that we inhabit are really frightening to me, as the politics are frightening. The notion of truth no longer exists. You make your own truth.

DUSTY SANG: If I understand what you're saying, the films of today will not have that durability over time. They will be sort of shelved to the side. Are there any filmmakers ...

JEROME CHARYN: ... not necessarily. For example, there was a film called Nomadland that I didn't want to see. I just didn't want to see it. And Lenore said ... and I said, "Okay, we'll see it." I saw the first three minutes. I said ... "I can't stand this. I can't watch it." Then we saw it the second night. By the third night, I was utterly fascinated. I said, "This is a new culture. These are people who are opting out of the world we live in." Remember, the heroine of this film has to leave her home because she's lost her postal zone. She doesn't even have a postal address. So, in other words, we live now in a culture of such incredible wealth and incredible poverty, that it no longer ... it's no longer a fixture that comes together. So the little films are going to be the films that endure. Not the big films. They're all formula.

DUSTY SANG: Will we get films out of this period ... about the pandemic? You know, with a pandemic and the economic dislocation, similar to the ones that were done in the Great Depression? Will there be novels that will be coming out that represent this period of time in an iconic way?

JEROME CHARYN: That's a wonderful question, Dusty, because this is what we hope. We hope that in some sense we will find that magical person who will be able to tell us what our own time is about. If you go back to the 19th century, the one writer who was greater than any other writer is Herman Melville. He tells us a tale about a whaling ship. And in that tale, he tells us about the whole sense of 19th century capitalism, and how that capitalism is going to fail through a captain and a whale. So we need some kind of mythologist in the 21st century to tell us, to give us a mirror of what our landscape is like. I believe that person probably exists. Who it is, I couldn't really tell you.

DUSTY SANG: You were quoted in the Columbia Magazine, and this is just by happenstance a quote that I raise to people all the time ... the beginning of Moby Dick, within the first two pages. It talks about Ishmael and his mood disorder ... you can see in it the bipolar disorder of Herman Melville ... and there is a great quote, " ... a damp, drizzly November in my soul..." and so he goes to sea because that is his antidote for pistol and ball. He's suicidal ...

JEROME CHARYN: Exactly. He's suicidal.

DUSTY SANG: Was that representative of that period of time? Or was that really Melville and his ...

JEROME CHARYN: I wouldn't be able to tell you. But if you go back to the literature of the 19th century ... we can't even read the literature of the 20th century because it's too close. We can't even tell you which writers are going to emerge, if they ever will emerge. If you remember, Melville was forgotten by the time he was thirty-six. It was fifty years or sixty years later that an obscure critic wrote about Moby Dick. And suddenly, suddenly, his world came back to us. So we have no idea of the formula. Nomadland was to me a revelation. And I hope these small films will exist and will tell us things about our time. For example, on the other hand, the film Mank, which tries to say that Mankiewicz was the great creator, a boss of Citizen Kane, is completely imbecilic. Mank did make a contribution to the film, but he was not Orson Welles. Orson Welles was the dynamiter of his time. If there's any filmmaker who will last, it's Orson Welles. He doesn't have to be the greatest. But he gave us a vision of how to make films in Citizen Kane that no other filmmaker, other than Tarantino, has ever been able to give us. He told us how a film has to be made.

|

| Jerome Charyn |

DUSTY SANG: Would you say that Steinbeck had the same impact ... was in the same position for his Grapes of Wrath as an example from the Depression era?

JEROME CHARYN: Yes, except he didn't have the language. If you look at Grapes of Wrath, it's a wonderful book. But the music, to me, at least for me, is not really there. So I don't feel the same feeling about Grapes of Wrath. If you go to Faulkner, for example, and The Sound and the Fury, you have absolute music.

DUSTY SANG: And both of these guys worked for Hollywood from time-to-time.

JEROME CHARYN: Absolutely. If you were a writer in the '20s, you went out to Hollywood, and Mankiewicz himself said, Come out here and they're idiots and they're millions to be made. Well, what happened to these writers? They went out to Hollywood. And I'm not talking about the so-called "Great American Novel" because that doesn't exist. But people like Nathaniel West did go out there and managed to write. And Scott Fitzgerald managed to at least begin The Last Tycoon, even if he couldn't end it. So it doesn't mean that there weren't writers writing interesting things out there. When Faulkner went out to Hollywood, he made a certain amount of money and then returned home. But you see, he was finished. And what people don't realize is that he was finished as a writer about the time he was thirty-six. All of Faulkner's great writing occurs at a very early age. This is also true of Melville. This is also true of Hemingway. It's really strange. If you go back to Hemingway, I mean, he was a great writer when he lived in Paris. He was a great writer when he was twenty-three. He was a great writer when he was twenty-four. He was a terrible writer when he was twenty-nine. Why? Why is there such a difference between The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms? Why is one novel so powerful? And the other novel, even though it's as great description of war, just an idiotic romantic fable? We don't know. We don't know why. What happens to writers. Fame is a destroyer of talent. It really is.

DUSTY SANG: Life intervenes. In some ways, if you look at the work of Albert Einstein, he had his great ideas when he was in his twenties.

JEROME CHARYN: Yes. And not only that, he wasn't even recognized. He was a clerk. He was doing all these formulas, not at a university, but as some kind of official in Switzerland. He didn't even have a position. He just had the genius. He just knew what to do. He knew what to do. And the same thing with Basquiat. You look at his paintings now. He is the great painter of the 20th century. You look at his paintings, and you say, "My God, what could have been inside his head? How could he have lived day-to-day there was so much inside there?" No wonder why he stopped painting. There just was too much there.

DUSTY SANG: He died very early.

JEROME CHARYN: Yes, because it was too much. He couldn't survive.

DUSTY SANG: So if we look back at this period of time, and I understand that Nomadland is something you identify as a kind of a milepost, are there any books that you've seen, any writers to keep an eye on who might be able to chronicle this period well?

JEROME CHARYN: I couldn't really tell you that. I have to do so much research for my own books that I'm not reading, that's my frailty, that's my fault line. When I was a kid, when I was in my 20s, I read every single serious novelist, male, female, whether it was Flannery O'Connor or John Barth. I read them all. I taught the first course in Contemporary Literature at Stanford. We taught the class at my home. We had 200 kids in my living room. They couldn't stop them from coming. They were so interested in knowing what was going on. Because, I mean, I was like a wild man, I'd read everything, and all these other teachers and read nothing. I knew, I mean, I could pick the book from the first sentence. I could tell whether something was going to work or wasn't going to work. And I don't have that gift anymore because I don't have the ability to sit down and read emerging writers. I mean, that's my frailty. That's my fault and you'll have to forgive me for that.

DUSTY SANG: Tell me how you met Georges Borchardt, your agent.

JEROME CHARYN: I met him through a girlfriend.

DUSTY SANG: His or yours?

JEROME CHARYN: The woman, who was my girlfriend, was an editor at the time and she had dealings with him. So we went out to his country home and we played ping-pong. Now, I wrote a book, and my agent at that time, I had a wonderful agent by the name of Candida Donadio, but she had an assistant and I went off with the assistant. And then at some point, she said, "I don't understand this book." So I went to Georges Borchardt and Georges Borchardt looked at me and he said, "I don't know if I can really help you." You know, he gave me a quizzical look. But he said, "Yes. Okay, of course, I'll take you on." And it's true. I mean ... I'm a strange writer. I don't fit anywhere. I don't fit in any quote ... school. I don't fit. I don't belong anywhere. I'm on my own quest. It's a private quest.

DUSTY SANG: The Charyn School of writing then.

JEROME CHARYN: Well, it's not a school. It's a school of one. With one follower.

DUSTY SANG: Can you tell me a little bit about Lenore Riegel?

JEROME CHARYN: Well, Lenore and I've had a very strange relationship. When I was young ... first of all, you have to remember I, as poor as I was, I had the best education in the world. I went to Columbia College and all we did, from being a non-reader, all we did was read, read, read, read. And in order to support myself, I became a substitute teacher. And if you were a teacher at one or two schools, you would be the first one picked. So I picked two schools – the High School of Music and Art and the High School of Performing Arts. And what happened is every time I was unlucky that I would take over someone's job, that person would get sick, and they would want me to teach for the rest of the term. And I had to do that. So at one point, a teacher got ill at Performing Arts, and I taught there and Lenore was one of my students. And she came up to me as if she were Mae West. And I said, this is a kid, I'm not, you know ... so we became friendly. And then she went off to college, and she had children, she got married. And then about 40 years later, she sent me, I didn't know what Facebook was ... some student of mine put me on Facebook ... and she sent me a note on Facebook. And I answered her. And then she didn't seem to answer back. So I said, "Lenore, are you going to fall off the face of the earth for the second time?" So she was so embarrassed that she answered me and we got together. And from the moment she came through that door, even though we weren't able to be together, we were really together. The moment she saw me ... the moment I saw her ... even though she had a job, and we can only see each other once. She was saying, Well, he must have other girlfriends because he's not seeing me on Saturday, he's seeing me on Thursday. Well, I couldn't see her on Saturday because I had my maid or whatever it was and I played ping-pong, or whatever it was. So in other words, we've been together ever since. It's a very strange romance. I remember we were walking in the street talking about it and a young woman was behind us. And she was fascinated by the story. She said, "How did you ever get together again?" It's just absolute luck.

DUSTY SANG: So you live in Manhattan?

JEROME CHARYN: No, I live inside my head.

DUSTY SANG: Well, Lenore lives in Manhattan.

JEROME CHARYN: Lenore doesn't exist. She also lives inside my head.

DUSTY SANG: So tell me how do you feel about New York now versus New York twenty years ago or forty years ago,

JEROME CHARYN: I no longer love it. I tell you that. If I were ten years younger, I would move to the country. I feel the discrepancy between the rich and the poor is so great. And I'm aware of this because I'm on the Board of my building and we have to put in new windows. And I'm the one who says, look, you can do whatever you want, but if people can't afford these windows, we have to find some way to help them pay for it. So it's just, Dusty, in some ways, it's too expensive to stay alive. It's expensive to die also. I know that. But in other words, we live in terrible times. It's just too difficult. It's too expensive. And so we have to find some way, some way to create a kind of order where people can really live their lives. You may not agree with me, but I this is the way I feel.

DUSTY SANG: Well, do you think that the country life offers those things?

JEROME CHARYN: I have no idea. It's another a fantasy. For example, all my life I wanted to live in Paris. So one day, like Humpty Dumpty, I went to Paris, and then suddenly I had a job, suddenly I had a girlfriend. Now, it's really strange, for a while in Paris, I couldn't write. For three years, I couldn't write a word. All I could do is play ping-pong so I became a ping-pong player. There's a musician, a singer by the name of Georges Moustaki, he called me one day said, "Do you know who I am?" I said, "Yes, of course. Your Georges Moustaki. How could I not know who you are?" "Well, your former girlfriend, the photographer, tells me you play ping-pong." "Yes, I play ping-pong." So from that point on, we played every day. And it was very interesting. We go to lunch and all of the women in the Greek restaurant would serenade him with his own songs. And I loved it, they would sing back to him as he sat there. And I had a great time, of course I didn't write anything. But it was a lot of fun.

DUSTY SANG: Tell me about your mother.

JEROME CHARYN: Ah ... my mother was incredibly beautiful, but incredibly narcissistic. And, as Lenore said, she didn't teach me how to sweep up a floor. I had a very ambivalent relationship with my mother. I loved her, but on the other hand, she was too vain. I mean, for example, when I married someone who wasn't Jewish, she wouldn't ... not only wouldn't she come to the wedding ... but she wouldn't allow my brothers or my father to come. And she made the excuse that it was my father who wouldn't allow it. So she didn't come to my wedding, but when she met my wife, she took these phony wedding pictures. And you can say, why was I passive about it? Why did I let her do it? Well, because it must have been out of a kind of residual fear. You know ... when you're five years old. You need your mother. And when you're 35 years old, you still have the same fear, you know? But she was really beautiful. You have seen a picture of my mother, Dusty. I mean, that picture doesn't do her justice. You could not go anywhere in the street with her without not only people whistling, but just coming up to her. And here I was this little kid with this woman. You know, I mean, it was amazing.

DUSTY SANG: So you're writing a book now about Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth. Does your mother remind you of the same circumstance that Rita Hayworth encountered because of her beauty?

JEROME CHARYN: Yes, in a way, but my mother looked more like Joan Crawford than Rita Hayworth. But it wasn't simply Hayworth's beauty. She was really violated by her father when she was a child. She never got over that. I mean, it completely ruined her life and, of course, she had early-onset Alzheimer's. But I didn't want to write about that. I mainly wanted to write about her relationship with with Orson Welles. And she fascinated me because her language was in the movement of her body. When I was gonna write a novel, I said, Well, I'll write a novel about Orson, but I couldn't use his voice because he was so full of himself. I mean, I didn't feel at ease. And then I couldn't use Rita's voice because she had none. So I had to invent a character to tell her story. But Rita deeply moved me, as Orson does move me too because, I mean, without him, we would not have the cinema we have today. We would not have people you know, like Stanley Kubrick, or we wouldn't have people who dared to decide that the film was an art, and they couldn't be greater than the machine that put them where they were. He was the first, at least in sound film, he was the first cinema artist.

DUSTY SANG: Of the people that you've written about ... everybody from Teddy Roosevelt to JD Salinger, Emily Dickinson, who would you say you admire the most or dislike the most?

JEROME CHARYN: I admire Emily Dickinson the most because people don't really know the details of her story. The poems that she published should never have been published because she meant to destroy them. In other words, she had such a rich interior life that she didn't need the admiration or the adulation of readers. She was a letter writer and she would put some of the poems in her letters. But her poems are also works of art, if you've seen the actual poems, and her use of a dash, I mean, she will write a poem about a house in the form of a house. So she is the person I admire the most. And her language, her use of language ... I mean, her genius ... it's something that I will never have, but it doesn't mean that I will give up trying to have it. So I learned the most from her ... that you could put any two words together and give them a kind of internal music. And she is the person I admire the most.

DUSTY SANG: Since our time is coming to an end, maybe we should conclude our Conversation on that note, because it's a wonderful note. It's been a great honor for us, Jerome. Everybody at Stay Thirsty Magazine thanks you for being part of tonight's inaugural program.

Links:

______________________________

Dusty Sang is the Publisher of Stay Thirsty Magazine.