Vol. 112 (2021)

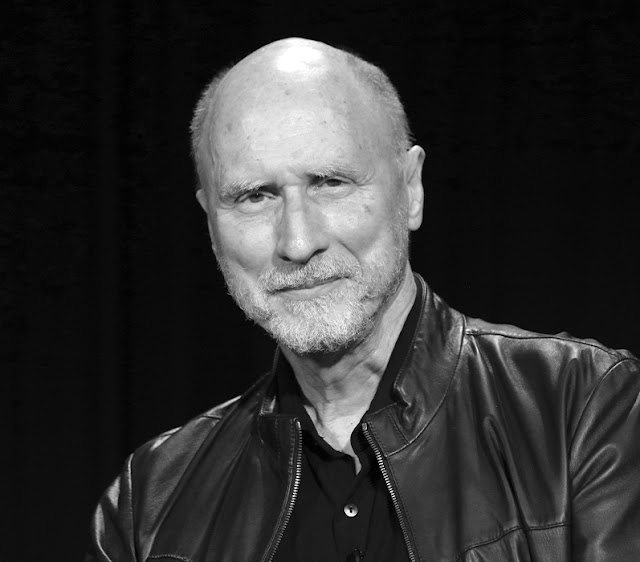

Five Questions for Pulitzer Prize-Winner Robert Olen Butler

By THIRSTY

Robert Olen Butler is a writer of astounding accomplishments. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction; the F. Scott Fitzgerald Award for Outstanding Achievement in American Literature; the Rosenthal Foundation Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award; twice won a National Magazine Award in Fiction and has received two Pushcart Prizes. He has also received both a Guggenheim Fellowship in fiction and a National Endowment for the Arts grant.

His stories have appeared widely in such publications as The New Yorker, Esquire, Harper's, The Atlantic Monthly, GQ, Zoetrope and The Paris Review.

With 24 works of fiction to his credit, his books have been translated into twenty-one languages and over the past two decades, he has lectured at universities, appeared at conferences and met with writers' groups in 17 countries as a literary envoy for the U. S. Department of State.

Currently, he is a Krafft Distinguished Professor holding the Michael Shaara Chair in Creative Writing at Florida State University.

Mr. Butler's latest novel, entitled Late City, has been called "a poignant meditation on the circle of life and the wonder we all feel as it slips away."

Stay Thirsty Magazine was honored to visit with Robert Olen Butler at his home in Florida for these Five Questions.

STAY THIRSTY: Your latest novel, Late City, explores a very old man's life as he is on the verge of death. Sam Cunningham, at 115, takes the reader on a journey through stories of love, fatherhood, career and the American century. It plays out under the umbrella of a conversation between Cunningham and God. How did this storyline come to you and why did you choose this conversation as the superstructure for your novel?

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER: I lived with engagement and intensity through more than half that so-called American century. Now I’ve lived another two-plus decades of the following century, one in which America, in 2016, dramatically expressed its longstanding dissociative mental disorder by electing—and I here struggle to exercise adjectival restraint—the President that we did, and then, four years later, by having 47 per cent of its electorate (an increase of 11 million) say Four more years of that, please. Sam begins to die ten minutes after that first election is called. Though the name of the winner is mentioned only just the once in the book, the event’s dark resonance was the inciting incident for my storyline. And for my feeling that it was time to look back to what brought us here. Not that this is a book of veiled political commentary. Nor a book of historical observation. Rather, it’s about the essential humanity that each of us is struggling with. Sam has lived his long life with similar engagement and intensity in similar realms of endeavor as I. The novel explores the enduring, deeper issues of the human condition, an essential part of which is that they must play themselves out most profoundly in the moment-to-moment events of our personal lives. I think the New Yorker reviewer wisely got that crucial order of cause and effect right in saying that Late City "warns of the political consequences of failures of personal insight.

STAY THIRSTY: Late City is boldly told in one long chapter. Why did you choose to organize the book that way? Is it the epitome of a grand dreamstorm?

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER: A fundamental premise of the book is that almost all of it takes place in a nanosecond, as Sam undergoes the passage of death. And in that nanosecond he must revisit and re-experience the crucial events of his life. So yes indeed, the novel is a sort of grand "dreamstorm," a term I coined when I first began teaching fiction writing back in the mid-80s. It identifies the writer’s inner exploratory process of literary creation from the artistic unconscious rather than from the "brainstorm" of the rational faculties. So it should not surprise anyone that the convention of formally labeled chapters in strongly voiced novels has often seemed artificial and intrusive to me. Sam dreams out the events of his life with the caesuras coming naturally and unformalized in its unified inner monologue.

STAY THIRSTY: Are there parallels in your mind between the comforting embrace of a mother and of a God?

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER: The image and trope of God is not just a glib or sentimental device but a sneakily important part of the larger vision of the book. So yes, a mother’s embrace is a part of that. But if and what comfort is attainable in this life before its end is a far more complex matter in Late City, as becomes clear when Sam and his full story find their release at the end.

STAY THIRSTY: In Cunningham's reflections on his life, what did he truly yearn for? What regrets plagued him to the end?

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER: Thanks for asking for my sense of Sam’s yearning. As you know, it’s a core principle in my 36 years of teaching fiction writing. Since Aristotle, we’ve understood that all narrative is about characters who have goals and objectives which are thwarted and challenged. For pure entertainment writing, those objectives can be simple. Solve the murder. Win the lover. Kill the monster. But for the literary genre I use that word yearning to indicate the deepest level of objective. And lately I’ve formulated a sort of Unified Field Theory of Literary Yearning (with apologies to Einstein). If you dig deeply enough, the yearning at the heart of every great central literary figure is a yearning for a self, for an identity, for a place in the universe. Why? Because that is the deepest yearning of every one of us on this planet. At all times we are struggling, in one way or another, to answer the enduring question: Who the fuck am I? So it is with Sam. Regrets abound for Sam as a complex consequence of the other crucial people in his life—wife and child, father and mother, friends and enemies—being driven by the same question.

STAY THIRSTY: With a total of 25 books to your credit, what is the literary legacy you wish to leave?

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER: My legacy will be a slippery thing if anyone tries to look at it in a generalizing way to sum up the whole corpus, which is currently 24 works of fiction. To a casual eye those books could even be seen as the work of four different authors. The seven books of one of those authors will no doubt someday generate the first phrase following my name in my obituary. Something along the lines of "writer of the Vietnam War." (Seven books.) But there is a "writer of humorous and surreal fiction." (Five books.) And a "writer of historical espionage thrillers." (Four books.) And a "writer of fiction chronicling the personal lives of the American twentieth century." (Eight books.) Even for any one of those four authors, those identifiers would be deceptively reductive. I am well aware that a writer—even a literary writer—benefits both in reviews and in sales by being consistently identifiable in those basic ways. This is an inevitable, even a natural thing. But if I had the power of wishing, I’d wish that my legacy would be seen as: He wrote books that eclectically spanned decades and subject matter and tones and voices, but the seeming restlessness of his shapeshifting was always in ardent search for an answer to the central question of the human condition. Who am I?

Link: